India’s political partition, when she plunged into postcolonial freedom, displaced more people more quickly than ever before or ever after. In only a few months of 1947 twelve million people crossed the newly created borders between what was to remain India and what would become Pakistan. Hindus and Sikhs travelled toward India while Muslims moved toward Pakistan. Before the Partition, my grandmother had lived in Lahore where her father ran a cinema theater. Once rumors spread about how murder and rape were meeting the movement of people between the two newly formed countries, her family fled. It was the wisdom of a man with nine daughters to worry about. Leaving behind familiar cupboards, kitchens, and streets, they came to Bombay and resettled with other refugee families in a tenement building. Refugees now, they could only afford to eat coarse grain that they had seen cattle eat in Lahore.

An old Punjabi saying goes something like this, “A man becomes humble when his daughter comes of age, his shoulders arch forward and he becomes vulnerable to the will of the world.” My grandmother says, laughingly, that my grandfather married her to lighten her father’s burden. My grandfather was a refugee too. He had come from Lahore in August, after the violence had begun, escaping to Bombay with a bullet wound in his thigh. His mother had been lost in the mayhem and only found in a refugee camp days later. He would wake screaming in the middle of the night for months afterward. My grandfather met my grandmother through relatives in the city. She was beautiful and he was besotted. Once he had finished studying and found a job, he asked her father’s permission to marry her. Her father agreed but his own family didn’t approve of the match.

She belonged to a lesser subcaste, they grumbled. Look how her bold older sister had already wreaked havoc upon her husband’s home, they glowered. He was too much in love with her, they worried in their hearts. A love marriage was as yet unheard of in their midst. An unexpected gift of the Partition, of the break from feudalism into freedom, of the city of Bombay. Gently but firmly my grandfather told his family he had made up his mind. He was both brave and tactful. Certain he wanted to marry this woman with whom he had fallen in love but determined to keep together the family that politics had already once torn apart. Cautiously, they warmed to her.

My grandfather didn’t want a dowry. He wanted my grandmother only, no jewelry, no trousseau, nothing the refugee family would struggle to give. No dowry, he insisted, even though at the time he had been suspended from his job for union organizing. Still, as he looked at the girl he had chosen to marry, looked at her fish-shaped sad eyes, looked at her smooth, young lips, looked at her bare arms, bare fingers, bare feet, bare toes, he must have wanted to make her feel like a bride. So he gathered what little money he had, knowing this frivolity would cost him and his young wife a substantial amount of comfort, and bought her his first gift. He shuffled awkwardly before her, unsure what she would make of his sudden extravagance amidst the scarcity of their refugee existence, and handed her a black satin box embroidered with red silken thread. Even before she saw what he had brought her, even before she had had a chance to marvel at how he had managed to turn the small amount of gold he could afford into wedding jewelry, she liked him.

And I, their granddaughter, born forty years after the Partition in the cosmopolitan metropolis of Bombay, cushioned from my grandparents’ experience by my father’s life between us, would think as a girl that my grandmother’s wedding jewelry in its satin case was a bit too grandiose, flat, light, broad, and much too ornate. Still, being her first born grandchild, it fell into my possession and when I saw it again last summer, a few months before my own wedding, I began to appreciate the romance of its hesitant extravagance. My grandmother is delighted when I tell her the wedding set is beautiful and I will wear it at my wedding. Her voice is scratchy as she says she knew I was the one who would enjoy her wedding jewelry the most, “You always care so much for the stories…”

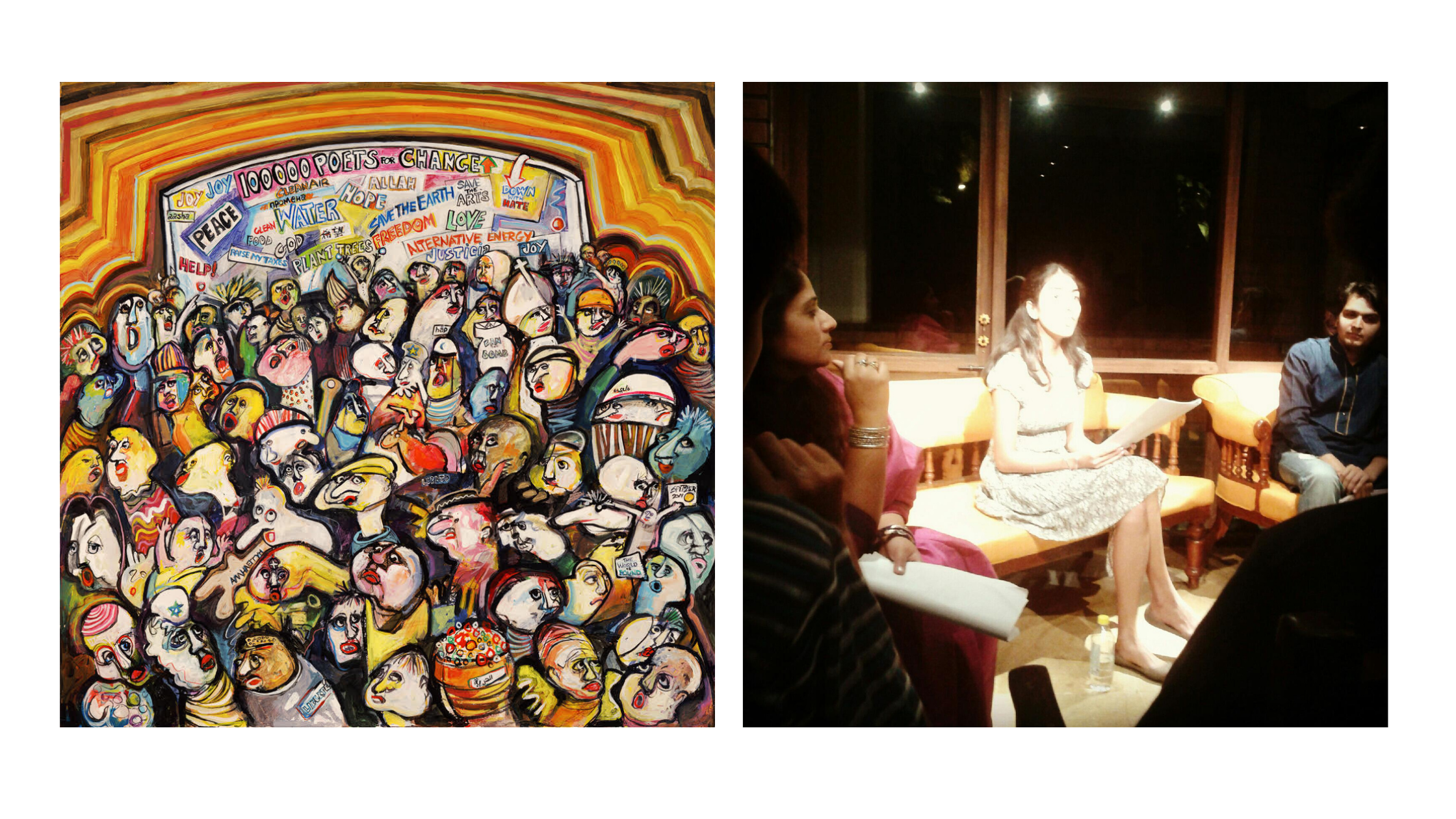

“My Dowry” was read as part of Bangalore’s 100 Thousand Poets for Change at Atta Galatta on September 29, 2012.